- Details

- Written by: J C Burke

- Hits: 11576

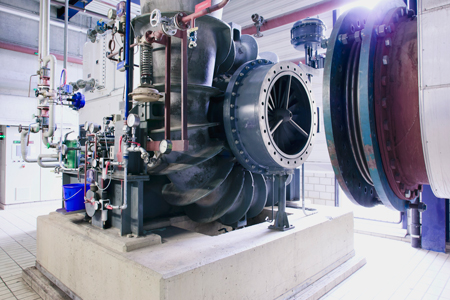

Combined Heat and Power (CHP) is not a new idea to the UK. Woking for example, has a large district heating network which makes considerable carbon savings and the Immingham plant on the Humber is a large industrial example. Yet when one compares the UK to Sweden, UK CHP seems very underdeveloped in comparison. Here we would like to discuss just what makes Swedish CHP so great and what the future holds in the UK for the technology.

Combined Heat and Power (CHP) is not a new idea to the UK. Woking for example, has a large district heating network which makes considerable carbon savings and the Immingham plant on the Humber is a large industrial example. Yet when one compares the UK to Sweden, UK CHP seems very underdeveloped in comparison. Here we would like to discuss just what makes Swedish CHP so great and what the future holds in the UK for the technology.

We won't cover the technical aspects to CHP cogeneration here, as just an introduction is needed. The principle is simple however; whether on a micro scale or on an industrial scale, power production and industrial processes usually create a lot of heat, which is wasted ''potential'' energy. CHP cogeneration aims to take this waste heat and make it useful, increasing the efficiency of the installation. Often this will mean piping the heat to nearby buildings to be used for domestic, industrial heating, or even, additionally [by the use of Absorption Chillers] chilled water for air conditioning! Known as TRI-Generation

Example of Sweden – wide adoption of combined heat and power technology

- Details

- Written by: J C Burke

- Hits: 6891

Notice that the methane levels have jumped up to 1800 ppb in the last 50 years [Blue Line] the global mean temperatures [Grey Line] used to mirror methane spikes, but now something else is happening graph source https://methanelevels.org

Notice that the methane levels have jumped up to 1800 ppb in the last 50 years [Blue Line] the global mean temperatures [Grey Line] used to mirror methane spikes, but now something else is happening graph source https://methanelevels.org

RECENT AND HISTORICAL DATA [Post 1983]

Since 1983, globally-averaged CH4 levels have been collected and updated monthly as new samples are added to the analysis. A 3 month lag is required to ensure the data has been properly vetted for possible contamination. Prior to 1983, methane levels have been extracted from ice core data from Antarctica.

Globally-averaged, monthly mean atmospheric methane abundance is determined from marine surface sites. The Global Monitoring Division of NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory has measured methane since 1983 at a globally distributed network of air sampling sites.

Credits: Ed Dlugokencky, NOAA/ESRL (www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends_ch4/)

METHANE

E. Dlugokencky, S. Houweling, in Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences, 2003

Biological Production

Decomposition of organic matter by bacteria under anaerobic conditions in, for example, wetlands, flooded soils, sediments of lakes and oceans, sewage, and digestive tracts of ruminant animals, involves complex simultaneous processes that can produce methane as a byproduct.

Read more: Rising Methane Levels - and impact on Climate Change

Subcategories

Heat Networks

Heat networks have been used in many parts of the World {including the UK - The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking opened in the 1950's as the UK's first true district heat network. This pioneering system connected 1,600 council homes to the waste heat generated by [the then] Battersea Power Station. The network survives under Westminster City Council today, serving 3,256 homes, 50 business premises and three schools.} to deliver "WASTE HEAT" {typically from the generation of electricty} to homes, businesses and public buildings/swimming pools etc. We see them as Combined Heat and Power systems {CHP} and in the UK at the moment there is 862MWe being generated with the correspondent Heat Network {theoretically at 1600MW}

Coming to a city near you - BUT NOT SOON ENOUGH it would appear

“Although heat networks currently meet approximately 2% of the overall UK demand for heating, the independent Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has estimated that, with continued support, they could provide 18% by 2050.” The Climate Change Committee (CCC)

Meanwhile in North London, the Bunhill CHP installation has now incorporated waste heat expelled from London's Tube Train network - Bunhill 2.

Meanwhile in North London, the Bunhill CHP installation has now incorporated waste heat expelled from London's Tube Train network - Bunhill 2.

In 5th generation networks, decentralised heat pumps draw heat from an ambient loop, meaning that excess heat can be removed and redirected to provide heat elsewhere. In this way, the system can provide both heating and cooling.

Another development in heating technology being tested is the ‘Internet of heat’. This is the idea that users could both buy and sell heat and energy, allowing consumers to become producers too. This could one day lead to local energy and heat markets, with distributed, decentralised micro-generation that would lower energy bills, increase efficiency.

Such schemes are key to overcoming the risks associated with establishing new heat networks, which currently acts as a barrier to realising their potential to deliver heat to homes. Retrofitting properties currently supplied by gas, in particular, is expensive. However in a 'new build' scenario, a Heat Network should be standard to maximise energy efficiency and thus minimise costs to the consumer.